History of Wolves in the Great Lakes Region

In Part 1 we explored how wolves can affect an ecosystem from witnessing their elimination and then reintroduction in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, but this concept isn’t far from home. How have the wolf populations fluctuated in the Great Lakes region?

1800’s

The hunt began. Wolves gained a negative reputation and bounties were being offered for their death. It took less than 40 years to eliminate them from southern Michigan in 1838.

Early to mid 1900s

Wolves also disappeared from southern Minnesota and Wisconsin, and by 1960 wolves were completely gone from Wisconsin, Michigan, and most of Minnesota. What was left was a only few lone wolves in the Upper Peninsula and isolated populations on Isle Royale. Wisconsin offered wolves protection in 1957 and Michigan followed in 1965. Minnesota’s hunt of all predators continued between 1965 to 1974, during which 250 wolves were hunted per year, causing their population to drop below 700 individuals.

Late 1900’s

In 1975 wolves were declared endangered in all the lower 48 states and were provided full protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). In Minnesota they were listed as threatened, allowing the federal government to kill problem wolves in response to depredation of livestock. The wolves recovered quickly over the next few years, and in 1978 they were reclassified as threatened in all lower 48 states. Approximately 20 years later, in 1996, Minnesota wolves were again reclassified as special concern due to continued increased population numbers and their range expansion.

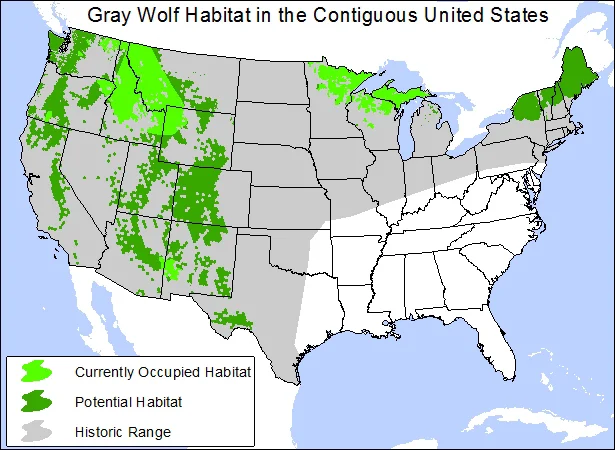

Map produced by Center for Biological Diversity

Early 2000s

In 2012 all wolves in the Greater Lakes region were delisted completely from the federal Endangered Species List. During this time open hunting seasons took place. However, in late 2014 it was ruled to reinstate their protection under the ESA; Minnesota wolves returned to being threatened, granting them management by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services.

Minnesota Wolves Today

Gray wolves are still currently delisted in Minnesota, but are listed as threatened at the Federal Status. Minnesota has the largest gray wolf population in the lower 48 states, coming in second only to Alaska. The Minnesota DNR’s most recent survey (2016) estimated there to be 440 wolf packs throughout Minnesota consisting of approximately 2,280 wolves. Their population seems to have stabilized with the abundant availability of prey such as white-tailed deer.

The gray wolf is an extremely adaptable animal, allowing their habitat range to extend into more developed areas that were previously believed unsuitable for them, and therefore they continue to disperse. This has increased the chance of human-wolf conflicts and raised concerns.

In certain situations, this is where Wild Paws may be able to provide a new home for those wolves who find themselves on the wrong path.

Because wolves have a long history of a false reputation as “the big bad wolf” we will educate how complex and special this species really is.

Wolves continue to have an important presence in our Midwest ecosystem to create a healthy environment.

Facts About Wolves

The more you know about wolves, the more your appreciation grows!

- Gray wolves can thrive in any type of habitat in the Northern Hemisphere including forests, prairies, swamps, tundra, mountains, deserts, and barren lands

- Wolves generally live to 6-8 years old, but have been recorded as old as 13 in the wild and 16 in captivity

- They are highly social animals living in packs of typically 7-8 individuals, sometimes up to 30; the pack consists of an alpha male and female that breed, find territory, and manage the hunting

- The alphas have one litter of 4-7 pups a year; they may allow for others in the pack to mate if resources are abundant

- Wolves are carnivores and consume a variety of large prey including moose, deer, elk, and wild boar, as well as smaller prey

- A hunt may last days, stalking a herd and waiting for the right moment to attack; wolves can sense any weakness or vulnerability of their prey with visual cues or sound and smell

- Each pack member has their own strategic role in a hunt based on their age or social standing

- Wolves are top predators in the food chain; their causes of death consist of starvation, wolf conflicts, disease, injury from prey animals, or human conflicts

- A study done on Minnesota wolves found that 80% of mortality is caused by humans

Show your support for Wild Paws' mission of rescuing and providing a safe habitat for wild animals using sustainable resources, promoting coexistence between humans and wildlife, and educating the public about the preservation of wild animals and their ecosystems.

References:

- "Canis lupus." Species profile: Minnesota DNR. N.p., n.d. Web.

Erb, J., C. Humpal, B. Sampson, and Forest Wildlife Populations and Research Group. Minnesota Wolf Population Update 2016. 2016. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, St. Paul.

"How Wolves Hunt." Living with Wolves. N.p., n.d. Web.

Service, U.S. Fish and Wildlife. "Gray Wolf Recovery in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan." Official Web page of the U S Fish and Wildlife Service. N.p., Dec. 2011. Web.